So, first, let's check out some pictures of both species side by side...note that these are not to scale - pics to show you how small the diamondback is lower down...

In fact, the diamondback moth does not have a pupal resting stage during winter - it's lifecycles continue all year long, but at a speed determined by climate conditions. So over the colder months, the life cyle may take 80 or so days, whereas in summer it will only take 30-35 days to complete a cycle from egg to mature moth. The time spent as larvae is greatly influenced by temperature, varying from 2-7 weeks. It will complete 6-7 life cycles in a year.

White butterflies on the other hand, are more effected by colder weather - they may complete as many as 5-6 lifecycles in the far north per year, but only about 3 in the lower North Island/upper South and 2 in the deep south. The cooler weather of autumn triggers their pupa to go into diapause, and they remain their chyralis stage for 3-5 months.

Controls

B.t and pyrethrins are other organic control methods that can be effective.

Parasitic and predatory wasps, praying mantises, lacewings, ladybugs, spider and birds are all natural predators of diamondback moth larvae, and in some cases, the adult moth. White butterfly caterpillars have a trick up their sleeve though - they accumulate mustard oils from their host brassica plants in their bodies, making them unpalatable to most predators, though some insectavorous birds will still eat them.

Encourage natural predators by growing a variety of flowering plants in your garden, and by providing natural habitats.

Nasturtiums are often planted as a trap crop - they lure white butterflies away from the brassicas. Nasturtiums are the only non-brassica plant on which white butterflies will lay their eggs. The plants can then be removed and composted (or given to chickens to pick through), eggs, caterpillars and all.

Learn to recognise the pupal stage of both species - and if you spot any at any time of the year, destroy them. The diamondback pupa will be on the brassicas - but the white butterflies seem to form their crysalises elsewhere; at least, I've never seen them on my broccoli, no matter how much they've munched the leaves!

Success with Beneficial Insects

The numbers of caterpillars did build up a bit in late Feb/early March to the point of exercising some digital control a couple of times (literally twice - that's all), but otherwise they were kept in check by the predatory beneficials to the point where they were of no major concern. Now, it was a colder, wetter summer than usual, so the white butterflies in particular were slower to get going, but the same principals of predation apply at any time of the year where the critters concerned are reproducing.

How to do that is not so much about focussing on these particular species, but by providing a beneficial-friendly-overall garden environment which leads to an increase in all sorts of beneficials, including these ones. Here are some of the ways I do this:

- Use NO sprays or poisons - even "natural" ones are generally harmful to beneficial as well as pest critters

- Plant a wide variety of flowers and flowering plants - the more the merrier. I major on edibles, but include others as well. My list is very long and I will post it elsewhere, but as a "sampler" I include phacelia, borage, rosemary, lavendar, buckwheat, calendula, marigolds, cosmos, zinnias, nasturtiums, lots of herbs like oregano and thyme, flowering fruit and vegetable plants etc.

- Provide water - shallow bowls with stones in them for bees and others to land on, and fresh water

- Leave some areas of the garden "wild"- abundant in thick and varied growth, which provides habitat and shelter

- Observe where your beneficials tend to overwinter, and provide and leave plants for this purpose. Eg ladybugs seem to particularly like to overwinter on spent corn stalks and under large silverbeet leaves.

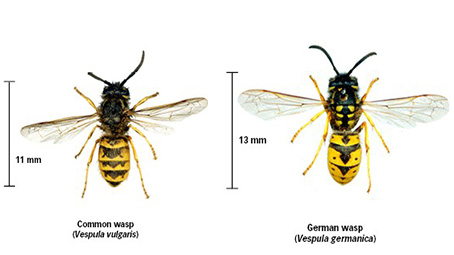

- Learn about breeding needs - eg drone flys, excellent pollinators, breed in water heavy in organic matter - so a bucket full of manure and water let sitting in a corner, with stalky material draped over the side to make an easy exit ramp for the rat-tailled maggots, encourages their breeding. On the other hand, I do draw the line at paper and German or commons wasps having nests in my garden - those I will kill. The odd wasp flying in and eating my bugs I'm good with, but too many where I'm working, wanting to protect their nests, is not ok for me - I'm allergic to the stings.

- Be willing to let some *pests* live in your garden - without those pests as food, the predators won't come. It takes a full and abundant ecosystem to properly support all things in balance.

- Never deliberately kill a species until you have identified it - learn to recognise the goodies and the baddies. And make informed choices. Eg, I know that the South African praying mantis is displacing NZ native mantises, and some would say to kill them. However, they are a major provider of pest control in my garden, and I've never seen a native here anyway. So I am happy to have them.

| This is a Harvestman, on my son's hand. Not a spider, it does not have a jointed body, and does not spin a web. It is a wonderful predator feeding on all kinds of pest bugs in the garden. Be careful not to kill any when harvesting or clearing parts of the garden - they tend to be found whereever there is lots of shelter and pests to eat. There are a number of different Harvestmen in NZ - this is the one I see most often. Harvestmen eat a variety of things, including: aphids, caterpillars, beetles, flies, mites, small slugs, snails, earthworms, spiders, other harvestmen, decaying plant and animal matter, bird droppings and fungi. |

| There are a number of different parasitic wasps in NZ. This one is Ctenochares bicolorus - and specifically preys on Green Looper caterpillars. I include it as an example of a parasitic wasp in my garden helping control caterpillars - this pic taken in my greenhouse, where it appeared shortly after green loopers started chewing on tomatoes and pepino - the caterpillars all subsequently disappeared and I had no further problems. |

Growing Brassicas Under Mesh

For completely keeping the pests away from your brassicas, the best choice is Wondermesh or a similar quarantine mesh. I bought a good amount of it from Lincoln's BHU, where they have done extensive trials using it to exclude psyllid from tomatoes and potatoes, and found it to also reduce incidence of blight and increase harvest size. With a 10 year life span, and allowing water and light to reach the plants, I find this fine mesh very useful in a number of applications in my garden. In the 2017/2018 summer, I am overhauling a large segment of my garden, and in the process am aware of the fact I am temporarily reducing plants and habitat that attracts beneficials. Therefore, this summer's brassica crop is under Wondermesh. Care needs to be taken to secure the mesh flat to the ground on all sides with no gaps, or the sneaky white butterflies will crawl in anyway (diamondbacks, despite their smaller size, seem to be less sneaky). Here's a couple of pics of my cabbages, cauli, broccoli, and kohl rabi under the mesh - interplanted with beetroot, and a couple of tomatoes at one end.

Timing

So, yes, these pests are not active in winter, but that is when the plants also grow their slowest or enter near dormancy (brassicas are essentially dormant when temps are below 10C). So to get good results at that time of year, one really needs to grow them in a greenhouse. See post on effect of winter temps on brassicas HERE.

Otherwise, some kind of protection from pests is needed - it's the gardener's choice what it will be. I prefer a combination of encouraging beneficials, timing some crops to avoid peak pest seasons, and using mesh covers as necessary.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed